(title matter)

"The Poems of Dorothy Molloy," and the ontology of titles in the music of Clara Iannotta

The parentheses would seem to suggest that a replacement is only inevitable. They weaken, to an improbable degree, what was merely a flimsy referent to begin with. As such, (title matter) constitutes no titling but merely the absence of one, a temporary stand-in for some as-yet-unseen but soon-to-be-found concrete name which will arise to fill the vacuum. It is too unstable. A title must come.

I can tell you now that this is not the case. There is no deferred replacement. In fact, it is the other way around. There was once a title, a very specific (and, I think, a very good) one which rendered as concise enigma all I wanted to ask about Clara Iannotta. Then I pulled it away. I will not tell it of you. I plan to leave that unadorned and indeterminate void in the place where the title should be.

This is an essay about what is already no longer known.

1.

Title matters, usually too much. It is the mark of a pervasive distrust in language that music criticism attaches so much significance to what a work is called: we do not believe in words unless they’re given to us first. Already insecure about its second-born status, criticism has immobilized itself on this perceived deficiency of medium, certain that the intractable concretization of blunt words will always be its limitation in the face of music’s infinite potential for meaning. Far safer to relegate language to the lesser and subservient but also less risky work of accessibility and translation (“here is what the music is trying to say or do, boiled down to a few clear and inoffensive metaphors”) than to hazard any serious speculative labor (which is to say: play). Hence the trope of “title readings”: beholden to a sense of medial inadequacy, anxious about brutishness, and determined to believe that music is always smarter than we are, criticism takes both too literally and too seriously the first scrap of language the work offers of its own accord simply because it means something. We are fast, in our embarrassment, to trust, too desperate to get things right, and in that desperation we make a blind assumptive leap wherein lies the real stumbling block: We mistake the something for everything.

To read music solely at the title takes as given the impossible premise that title and music are always achiral, that they refer exclusively and with perfection to one another. Extrapolative title readings do not leave room for any difference. Today we will not take that given. Today I want to think about nothing other than the possibility and consequences of that difference.

—

The difficult reality is that name is functionally both less and more: It is only (and this is a lot) the gamble by which music wagers the assembly of its truth. That it is so easily legible—as in, able to be read and thus to permit reading (which is what good criticism hopes to do)—is simply the necessary consequence of the laws governing a title’s distribution in space. From Derrida:

“There is no title without legibility of a trace, there cannot be a purely phonic title without possibility of its being recorded and without a code of legibility, Legibility, I specified, of the title having to be somewhere: by that I imply no theory of the title can be rid of a topology. No title without spacing, of course, and also without a rigorous determination of a topological code defining borderlines. A title takes place only on the border of a work.”

As regards music—a subject Derrida skirts in his essay, favoring literature (a medium which conveniently shares with its title a code of articulation to which music is not privy)—the topology is twinned: that of space, yes (the score, titled like a book is on the empty white non-space of the cover and, again, in the thin upper margin of the first page of notation [though this need not necessarily be the sole border; think of the elliptical titles below the last bars of Debussy’s Préludes]), and also that of time (in the dim and weighted silence that settles just before a performance begins, I glance down (with urgency, I need to know) at the looseleaf program floating haphazardly in my lap to confirm the name of the about-to-be-heard piece before I hear it). At both thresholds of the music’s becoming—the start of reading/playing or of hearing—is placed a screen of expectation, knit by language, meant to condition the associative imagination through which I attend to sound. In the rare instance when I am asked to listen without first knowledge of the title, I am disoriented and uneasy to the point of distraction, unmoored in the face of music’s infinite capacity for possibility. That the music gives a title before I hear it in some way entitles me to it, and that title—and the degree to which I can comprehend it—permits or refuses potential avenues of reception and interpretation through which I will/can forge a relationship with the sonic material. I can think through this music at all because—and this is the enthymemic leap on trial here—it offers me the first words for doing so.

(Last edition, for instance, we unpacked Rebecca Saunders and her relationship to Ed Atkins’ “Us Dead Talk Love.” She has a piece which shares that title but does not use its text. The fragments sung by the contralto are borrowed entirely from Atkins’ “Air for Concrete” instead, making the title a counterfeit, a hoodwink, a misappropriation of the material origin. But look at what it does to critical reading: a woman sings; she curses, squeals, groans, spews; the piece is called Us Dead Talk Love: meaning, intended or otherwise, will not fail to be extrapolated; assumptions are already being made.)

—

Title matters—etymology from Latin materia, “substance from which something is made,” preceded by Latin mater, mother, originary, birth-giving. Title mothers.

—

If the ocean of all critical possibility unfurls at this shore, it must inevitably break against that sand on the tide’s return (title/tidal matters). New violence in the round-about (Derrida again): “A title is always an economy awaiting its determination, its specificity, its Bestimmtheit, what it determines and what determines it. Determining and determined, determination always returns to it.” Just as the work is inexorably formed by what we call it, the title at the end can no longer mean the same as when we began. The title of Cassandra Miller’s bel canto conditions a set of expectations at the top of the score—suggestions of affect, material, and style, historical contexts, modes of listening—which are scrubbed and reconfigured by the final bar. The determination of the title, summarized simply as “What is bel canto?,” changes with duration, shifting towards unexpected peripheries. And so the title’s legibility contains this certain force, this “violence of the ellipse” by which expectation and experience spin round on the same axis to enact with coeval force on work and name.

Title–Matter; along the en dash, a bidirectional current of signification. ↔.

—

And, finally, titles matter: in the first edition of this series, I wrote about the role composers play in the custodianship and upkeep of their own critical discourse. And while a composer’s reading is not necessarily the sole (nor even the most productive) interpretation of their work, it is from their trail of spoken and written breadcrumbs that discourse begins to fumble towards an understanding of the music which supersedes the mechanics of its construction or the means of its production. Titles are the most visible of those linguistic keys, the first handrail, toy abecedarium, the training wheels. The more of them criticism can accrue, the higher the relative porosity of the compositional project, traceable evidence of patterns emerging in how the music refers to itself. Radically redistributed by title along the brutal logos of the alphabet, the ordered catalogue of works is like a monstrous reference dictionary, a series of organized hints meant to betray the music’s sense of self to external scrutiny. This toponymy of titles is, in no small part, how sensibility burgeons into oeuvre, a map to how the work (general) thinks about the work (specific).

For example: the blunt atomic materiality of Enno Poppe is, before the music, in his titles: Öl/Speicher/Salz/Arbeit/Schrank. His predilection for these single, elemental words is their potential to generate endless chains of possible interpretations from a single semantic unit; his music does the same. Or the pressing queer substantiveness of T McCormack’s music, there in its titles: yours in the process of being absorbed/mine but for its sublimation/deep terrane (earth dreams itself, sweating) invoke the vulnerable and shuddering intimacy of bodies weighted heavy by the intensity of their emergence. Or there is always the option to refuse poetic singularity of “the work” altogether and leave open the universe of output-relations to the power of pure sequence: Éliane Radigue’s Occam I-XXVII are all cut of the same cloth, the only difference being the infinitesimal gap separating I from II, which is to say everything.1

—

This is a small theory of how titles matter: how they generate meaning by topological necessity, change under violence of determination, and serve as both the stepping stool and stumbling block of a music’s entry into language. Criticism, bound to words, suffers heavy at the hands of titles, and yet still cannot do without them: they are our curse, and also our purview. We know, and cannot escape, that titles matter.

The rest of this text will be a matter of degree.

2.

For the last ten years, Clara Iannotta has excised every one of her titles—without exception, true preposterousness—from the poetry of the Irish journalist Dorothy Molloy. Her first work to do so, written in 2013 for Trio Catch, takes its title from the refrain of Molloy’s “Tramontana.” There are three stanzas to the original poem, each with the same ending (this is the first):

Tramontana

In Cadalqués the women with red arms and pickled hands

salt anchovies.

The fishermen, marooned in bars, smoke fat cigars; play

chess and dominoes.

The tramontana rattles doors and shutters. Waves crash on

harbour walls.

The people here go mad. They blame the wind.

—and while it has always struck me as a very good title—in the sense of being both succinct and evasive, suggestive without leading on, sound-full but not yet sonically prescriptive—I have often wondered whether it is the right one. Not that it feels incongruous; the opposite, actually, the phrase lends itself generously to metaphor. But it is the become-metaphor of which I’m suspect, uneasy in my knee-jerk willingness to invoke meaning where I’m not totally convinced there is one. Reading for madness and wind feels too easy, too obvious. The music—or a part of it, at least—recoils from simple equivalencies. What is that tug of resistance?

At this point in her career—2013—Iannotta essentially has her sound bank nailed, and in the ten years that follow, her material interests will remain more or less the same. They will gradate to finer degrees, and they will also slow down tremendously (mad/wind is one of the last works retaining any solidity of gesture, banished with finality in 2014’s you crawl over seas of granite), but the core sonic values—the preparations, the palette, the instrument families, all in search of sounds from which the body has been removed—will hold firm. And they will do so to an absurd degree: within six years Iannotta will be returning to her previous works and dehiscing new pieces from inside the skeletons of old ones. She is, in all ways, uncommonly cathectic: these are her materials, she sticks to them.

Again, I’m not suggesting that the title is somehow inconcinnous to the music, but expressing an interest in how her titles are capable of such considerable shifts in imagery while the sonic material is permitted to remain so economically self-contained. Chasmic differences of place and affect separate phrases like They left us grief-trees wailing at the wall; paw-marks in wet cement; Troglodyte Angels Clank By; dead wasps in the jam-jar; and The people here go mad. They blame the wind. The music, on the other hand, is only subtly differentiated. What, then, is the mark of haecceity that individuates works enough to warrant this title and specifically not that one? What permits them to hold fast (or, relatively so) to their names without slipping into interchangeability?

Asked another way, the crux of the thing: can they?

Can “they” blame the wind? We have to ask. In the music, which the title determines and which is determined by it in turn, are there people, do they go mad, and is the wind responsible? Is it that simple? Does sound establish and maintain a durable-enough bond with the designating phrase for the experience of the piece to be productively reduced to the antecedent-consequent relation in its name, or is the title just a well-phrased poeticism whose power of suggestion was strong enough to evoke a sonic landscape with behaviors more tangential to its nomination? Is it really enough to call the music boxes madness? Is it really enough to call the cardboard wind? Can the piece be said to be about—programmatically, metaphorically, poetically even—any of those things? And, more broadly, is it in the law of titles—this title—to formalize discursive positions in sound, or is name related to sound here by more obscure codes of conjunction? Which is what I meant by ontology: does the title take adequate hold in the music, enough for us to say it is there?

What I’m getting at is a scrutiny directed toward the contingency between title and material, a thinking-through of the possible determinative relationship that does or does not take place in Iannotta’s music. I am interested in the argument that her work sets up for or against the images laid out in its names. I am curious about its truth. You could also say I’m posing a rather straightforward inquiry: does the title matter?

Let’s eliminate first the obvious: title-as-matter. The nature of the musical material seems to preclude the likelihood of a program or some narrative circumstance borrowed from the poem’s locale. Where Saunders’ Yes is gleefully inseparable from Molly Bloom’s refracting interruption (to pick an example), Iannotta’s work seems to have relatively little interest in its source. She is not in the habit of copying the complete poem into the front matter of the score or excerpting it for the program note. She will merely hint in passing that “the title comes from a poem by Dorothy Molloy,” which, turning now to the hazy nature of the music, seems intentional. Molloy’s scenography clarifies to an almost banal degree all the shimmering opacities that the title on its own holds in welcome uncertainty. Theoretical illustration of reinstating the poem:

—who are ‘the people’?—women, fishermen, locals, and, Molloy will later say, “I.”

—where is ‘here’?—we are in Cadalqués, on Spain’s border with France, nestled in the juts of the Cap de Creus and upturned to the waves coming off the Mediterranean’s Costa Brava.

—which ‘wind’?—the tramontana, the northern wind.

In the poem, these are truths. The musical material, however, attempts absolutely none of that specificity. There is nothing in the music to suggest a location—no flavor of Spain, no cigar smoke or red-raw hands—nor is there a wood made to rattle by some blustery force, no climactic wave-crashing or sound of the sea. The piece is something else than the poem: a gradual calcification by which loping, cyclic rebounds—piano harmonics and light cello tracings amid a wash of stumbling music boxes—rust into aerated and frigid stridor. As the music drains off its glittering interior, it tenses, a hypothermic and empty shuddering interrupted by toneless clicks and prolonged static pitches. Only once, at the end, does the gossamer material reappear with any reinstated body, but only for a fraction of a moment: three enormous gusts of exertion cut the glance—and the piece—short.

To the question of wind: as in the ending, there is plenty in the music to resemble windiness—breath tones, whispered half-harmonics, long stretches of toneless bowing—but they do not function discursively as they do in the poem. They are not offered syntactically as an external force battering against and changing for the worse a defenseless plaintive Other. What sounds “like wind” (from a simple reductionist standpoint) only emerges from the emptying-out of previous material, not a fixed condition but one discovered: windiness is a provision internal to the work and dependent on form for its emergence. The poem in toto and the scenario in which it takes place thus have no formal (surface) solidity in sound.

So then, if not the sonic specificity of its context, we need to know what draws Iannotta to these particular moments in Molloy, because she does have preferences. Reading Molloy for long stretches turns up lines that aren’t Iannotta titles but feel like they ought to be [and that is what I mean by preposterous], which suggests that she does not cherrypick titles indiscriminately. She is guided by a sensual attraction to certain of Molloy’s devices that contain an oblique Clara-ness. More often than not—around 65% of the time, though the two premieres next years will skew the balance toward center—she prefers final lines, as in Molloy’s “Passage”, whose last four lines became an Iannotta title in 2020:

Passage

The teased-up earth

settles.

Nettles sting

in the ducts.

We buried you

today.

Firmed you

in.

The grass seed is

down.

The water

poured.

There is a stir

among the stars:

a cosmic shift;

a making way.

Here it is more obvious that Iannotta’s predilection for Molloy’s closing lines has nothing to do with finality, but with a sense of expansive darkening towards which Molloy’s poetry moves that is often, but not always, found at the end. Molloy writes with binoculars: both “Passage” and “Tramontana” demonstrate a tendency to hone early on a quotidian image—often one splashed with implied violence or perversion, some degree of hinted unsettledness—only to pull the binoculars sharply away and reveal a vast surrounding darkness that has been pressing unseen on the edges of the image, giving it shape but held at bay by the intense economy of her details. With that proximity rescinded, the darkness rushes in, and the place of specificity where the prior image could retain its structural integrity vanishes into immensity, leaving only an impression of where it had once been: the burnished but temporary and already-dissipating imprint on the eyes of a solitary focused light suddenly switched to off.

In “Passage,” the final stanzas cast out to a place where the initial image of a burial is hardly visible, or visible only in the receding memory of its momentary glimpse. On their own, the lines “There is a stir/among the stars/a cosmic shift/a making way” have no obvious relationship to funerals. On their own, they are merely lovely. Their soft catasterism is made possible only by traversing past—and thus sensing, at the level of flesh—the sudden stoppage of the death’s hum that pervades the first three stanzas but ends abruptly before the fourth. The shift in that line-break is geologic and final: nothing previously concrete is allowed to pass that threshold. Death echoes, but it does so only in the kernings, the spaces, the silence; it is by the knowledge of having been there that this unrelated here makes sense at all. The same is true of Iannotta’s you crawl over seas of granite. That line serves, in Molloy’s poem “going your own way,” as the first hint of drowning in a poem that began as an evening swim (the last stanza will read: “you lean on waves of cold/comfort before/going/down”). Everything preceding that line is a casual swimming out; crawling and granite are the first shivers of the undertow, the simultaneous sinking down only just now being registered.

In borrowing for her titles these peculiar moments of scaling-out, Iannotta seems to be quietly suggesting that her music begins at the place where Molloy’s poetry tends often to leave off: in the slow readjustment of perception to the heavy shadow encroaching on a now-vanished point of specificity, the instant of darkness when significance is wholly reliant on memory’s fidelity. The problem, however, is that she borrows them for titles, where they point forward to music, rather than back towards words. Back to Derrida’s code of determination, how are we meant to receive these transient images of loss as titling when they’ve been shedded from the source whose submerged violence gives them their implied force? “The people here go mad. They blame the wind.” means most in the passed-through context of a poem about sea-battered Cadalqués. Iannotta does not offer us that context. What then—if anything—does the poetic (as in: initial) understanding of the line have to do with the music?

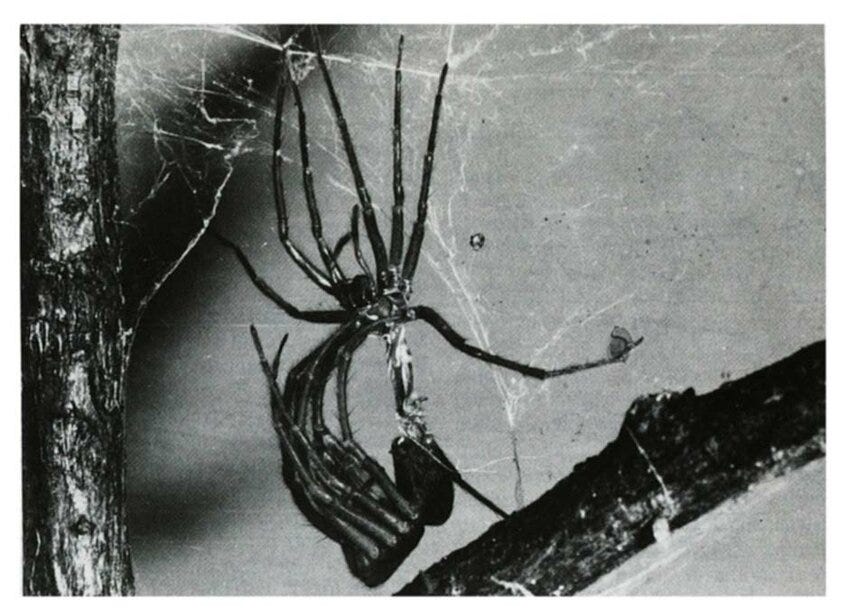

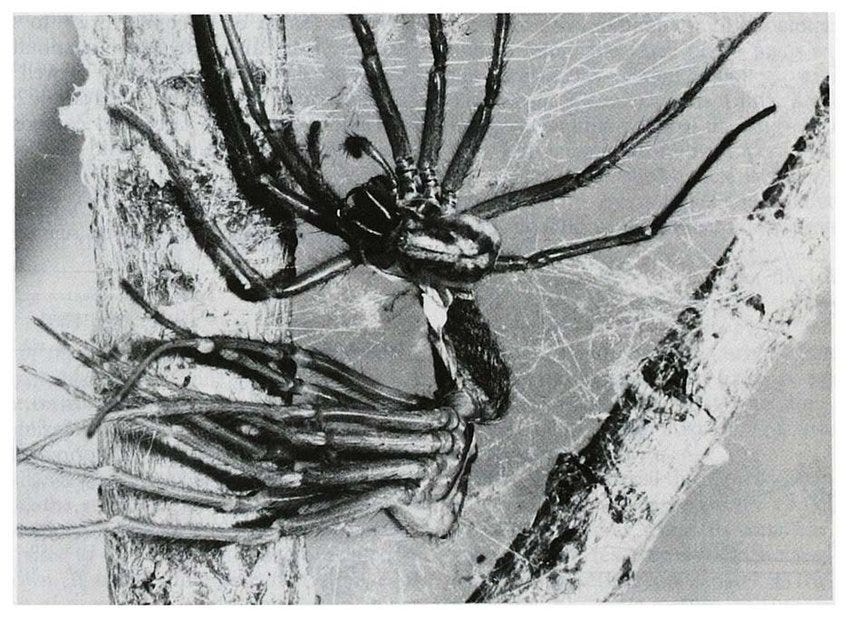

In her 2021 lecture at Darmstadt, Iannotta talked mostly about spiders. MOULT, for orchestra (notably the only one of her works which takes the actual title of a Molloy poem, rather than a line, as if suggesting that this piece is more substantive than a single faded impression [a suggestion which has proven overwhelmingly true; she has since siphoned three further pieces directly from MOULT material, as well as the phrase eclipse plumage, which comes from the same text]) began as an inquiry into the formal possibilities of leaving an old bodies behind. In arthropods, the process of shedding an outer layer is called ecdysis. It is an intensely traumatic and violent operation, requiring several minutes of pain and suffocation on the part of the insect, during which they are deeply vulnerable and defenseless. When ecdysis is complete, the arthropod, still freshly soft and sticky, will abandon the empty casing of their body and move to more protected ground to harden before taking leave of their old body completely. Those left-behind shells are called exuviae, a word transferred wholesale from the Latin, where it means things stripped from a body.

The spider analogy isn’t new territory exactly, only a sharpening. Iannotta has been centering her music in experiences of resonance and physical memory since before her engagement with Molloy (most explicit in the loose trio of works inspired by the echo of the Freiburg carillon, where, again, titles reveal much indeed: the second of the series is called d’après, literally after. [In this vein, it’s also worth mentioning A Failed Entertainment, the string quartet immediately preceding mad/wind: it borrows the abandoned working title David Foster Wallace gave to Infinite Jest {sloughed-off material, a trace of what is no longer visible, an unmoored memory of what now exists in another (stronger?) form elsewhere}.]) Iannotta was fixated on what is left behind long before she found Molloy. This new and acute notion of exuviae is, however, exceptionally productive for framing that work, and, specifically, as it related to her entanglement with Molloy.

Things stripped from a body are, in many ways, the state of her titles. They are what the vanished poem leaves behind as emptied trace of its meaningful self (the complete text of a poem is, not for nothing, called its “body”). Lingering but incomplete, suggestions of former form: in the single line, cut away from the rest, a vision (however fleeting) of the whole. They are also, as I demonstrated earlier, moments of seismic internal shift, lines along which the poems recast and reform their previous selves toward darker (more mature? heavier? more defensive?) places. Together, this makes the obscure image in an Iannotta title not a solid thing at all but a thing both in the act of pulling away and also a thing pulled away. Iannotta’s titles as titles (as distinct from lines in a poem) are thus not images but contingencies: what they suggest toward the music is a relationship between the act of imprinting and the imprint, between the leaving behind and what is left. They are, to use Iannotta’s own metaphor, the very thing which binds exuviae to ecdysis.

This last suggestion is specifically meant to exclude the living insect from the equation. I’ve never once gotten the sense that Iannotta’s music is invested in the futurity of a becoming. Trapped as it always is in states of recession, there is little room here for the breath of triumph of a new-young spider. But bracket the arthropod to focus instead on shell and shedding: The intense violence of ecdysis by which exuviae become the very thing they are is never again accessible to them, the shell by definition newly body-less and thus sense-less. It, too, undergoes a moment of acute suffocation and breakage, but where the insect goes on to new growth as a result, exuviae persist only as a relic of that trauma without the means of reaching again the very thing that gave them form [matter, materia, mother]. The presence of that inaugural cleaving can still be felt—quite literally everywhere, it is a document of the former experience of trauma—but then only in an impression which retains no living trace—it is a document of absence, it is a nowhere. Exuviae are the accessible memory of a complete, absent, and inaccessible ecdysis: trauma’s cenotaph.

Which is how—returning finally to the inquiry that set us adrift in the first place—Iannotta’s titles can rove while the material so insistently recourses. Across the Molloy corpus there are only a small (albeit brutal) handful of “original pains:” the death by drowning of a young sister, the death of a dog, a barely-glimpsed rape, and, overwhelming at the end of the collection, the discovery and failed treatment of liver cancer that took her life in 2004. Molloy’s work shifts its weight around and away from these recused incisions of violence, hinting toward them in residues and echoes without ever facing them head-on. They are always there, constant but rarely seen, already several steps removed from tactility but hovering under everything.

The lines Iannotta chooses, we know, are points at which the space surrounding a particularly resonant image darkens into something strange and huge, the very moment at which trauma is no longer visible but felt. As a collection of titles, their poetic importance shifts from literal contextual specificity to the varying degree of achieved proximity to that removed and distant violence. Some get closer, some stay at a remove, some look to the heavens, some peer into the abyss. The violence towards which they cast, though, rarely changes: it only moves.

“We are confronted by the physical trace of the past within the movement of the present, a vision of the self split across time.”

(from Iannotta’s lecture)

Earlier I asked: “How are her titles capable of such considerable shifts in imagery while the sonic material is permitted to remain so economically self-contained?” Here, at last, an answer. Like the title, the music is also an exuviae, shell of some unspoken violence which has already taken place and lingers now only as memory, trace in absence. It is thus also the same body across pieces, the same marked violence which gave it shape and towards which it casts. But the local identity of that violence changes each time, marked out by the variation in the titles and then their subtle reflection back onto the music. As in a life: old violence recasts itself in weird and unexpected crevices. Wherever it finds one, the music reaches obediently, instinctively—as exuviae do—towards these empty origins which it knows it cannot reclaim. The reaching takes different forms, different intensities, differing hacceities. But the what towards which the music reaches is unchanging: it grasps at something once had, something that formed it as it took its leave, an ecdysis to which it cannot return or even know but will always seek: that which it is.

The title is a recovered moment of loss, cut away and hung in time. The music is the act of reaching through that darkness toward the blinding infinity of degree zero and finding it once again unreachable, there only in the place where it is no longer.

3. loose ends

The people here go mad. They blame the wind.

Can they blame the wind?

First, take the title formula as determinative (it is permitted: Iannotta’s titles are not not images; they are also, at the level of text, the thing they claim to be). We may assume, following the grammar, that there are people, they are “here,” and they do go mad. We may also assume that yes, they can blame. Of course they can. And they will go on doing so, mad people blame their madness on many things. They will blame the wind. Only the wind itself is not an ontological given. We do not, or rather, we no longer have the contextual decisiveness afforded by the poem. In the line-as-title, thing stripped from a body, decoupled from the form-giving source at the very point of decoupling, the wind is only the object of a floating accusation, a suspicion without the affirmation of its truth. It is a (real?) memory of wind, a theory of wind, a windswept-ness without the tactility of moving air as proof. The somatic surface of the sound-body bears trace resemblances of having once come into contact with something like wind, but the wind itself (if indeed it was wind at all) is long since gone, somewhere unreachable and beyond accessibility. (The music boxes never arrive at recognizable melodies or quotations, only hint at their assembly; the sound of nostalgia without the object of its longing, nostalgia for an unspecified and inarticulate past.) The bodies bear the lasting behavioral impression of having once been subjected to a force great enough to induce madness, but the force remains a constant and inaccessible obscurity.

The people here go mad—that much we know—they blame the wind.

Whether or not there was wind is the endless unanswerable. We can term that irreducible “wind,” or really anything else for that matter, but its resemblance to windiness is largely irrelevant. The only real concern is the weight you place on what a thing is called. What matters is if title matters.

—

(The title of this essay, before I rescinded it, was “The Culpability of Wind.” That cannot mean anything now. It is not the title and it does no titling and so it determines [signifies, means] nothing. Doing so, it means everything.)

Housekeeping:

First, and really only, happy holidays. This space, and the attention, love, and patience you have offered to it have been one of the highlights of a very heavy year. I’m intensely grateful for the opportunity to share things with you here, and to have been so generously and continually supported along the way is the greatest gift; thank you for it.

To that end, I’m sorry it’s taken rather longer than my ordinary month to get this out. Since Preposterous Reading began, my desk has become (and gratefully so) far more cluttered with deadlines and assignments that now require me to split my time (read my Evan Johnson/Eugenie Brinkema profile in VAN here; lots more there in the coming year, including a profile of one of my favorite Berliners next week). It is a welcome problem, but it has meant that Substack sometimes gets back-burnered—which is a shame, because it’s really the format I love the most. Know that I am always wishing and thinking toward my next (and often two beyond it) post, even if they don’t appear quickly. In the New Year (resolution, trite, blasé, destined for failure) I’ll try to be more proactive. Try; I promise nothing (preference anyway for speculation, play, “reading without promise,” &c, &c).

All that said, this publication puts us back on some semblance of a schedule, which means Enno Poppe and Marcel Beyer are up next. In that essay I’ll be reading Beyer’s The Karnau Tapes (feel free to follow along), though I also have a copy of Kaltenburg lying around here somewhere, and will likely reference both; as a pair, they’re worth the investment. It’s not often I read WW2 fiction—even less so by a male-identifying author, and with a masculine protagonist—but I’m surprised to find I’m rather enjoying it this time around. Marcel is very good at what he does. And it helps I’ve been on something of a Poppe kick lately. I revisited Prozession on a drive to work last month and had to pull over and call Kelley Sheehan in a daze to gush about it (her kindness after all these years is to not roll her eyes). Enno is underrated, and while his ability to find forms that feel both fresh and surprising and totally idiomatic to his material routinely floors me, Prozession goes one step beyond that. It has one of those rare moments when the form lurches up and staggers into a dazzling place that shouldn’t have been possible from the material alone, a kind of I didn’t know you had that in you, right at the end. I’m still not totally sure what I’ll say about Marcel in the context of all that, but then again, that’s why we do this.

And a few light updates: since last I wrote, there has been considerable travel—Ithaca, Chicago, New York, London, and tomorrow to San Juan, each trip containing the seed of some future project. Chicago was the highlight, for a pair of pants that I’ve worn almost daily since returning, but London had its upsides (a fabulous Guston exhibit, on until February at the Tate Modern). Between trips I’ve read Anne Carson, Clarice Lispector, Cesare Pavese, and a short Joseph Osmundson text I liked, but didn’t love. In my Puerto Rico bag, I’ve got an old copy of the Beckett novel trilogy (a brush-up for a chapter on Liza Lim in a collection of essays with Lyrebird Press, coming out in 2025), Sianne Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories (on recommendation from S.B.), a little Fleur Jaeggy (my beach read), and the Beyer. I won’t get through it all, but I find I’m comforted just having the options on hand. Before all that, though, Gramm and I have plans to catch the new Lanthimos movie tonight. I’m beside myself.

With that: happy holidays, and thanks, both for the patience as I got this written and, as always, for taking the time to parse it. May the days of rest ahead bring warmth and comfort to you and yours.

you know this I love you

-tb

Notes:

Derrida, Jacques. “Title (To Be Specified),” trans. Tom Conley, SubStance 10, no. 2 (1981): 4-22.

Iannotta, Clara. “Moulting Spaces.” Darmstädter Ferienkurse, August 7, 2021.

Molloy, Dorothy. The Poems of Dorothy Molloy. New York; Faber and Faber Press, 2019.

Images from Collatz and Mommsen, “Physiological conditions and variations of body constituents during molting cycle of spider Tegenaria atrica C.L. Koch (Agelenidae),” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 52 (3: 1975): 465-76.

There is also a more sinister variety of sequential titling, one which gives lie to a music whose function is solely as fixed-value product, sellable as a prepackaged and consistent commodity, and thus reducible to a series of minutely-differentiated iterations (in the same way that we are on iPhone 15). The insistence of their titles mimics their safe sonic predictability: “My music does this one thing, it does it very well, and it does not risk anything else; it will be exactly what you want it to be, that thing I do, just like all the rest of it. For a convenient curation experience and total commissioning safety, click here!” Branded composition and market-ready music is a form of art-as-capital, fodder for an institution which demands newness but does not want to be confronted by that which it does not know. Titles can be cruel and indiscriminate that way. (See Mouthpiece)