tender contingencies

on form, proximity, texture, and Richter. featuring a fly.

One month in and I’m breaking my promise. I had said it would be Saunders and Atkins next—I even read the book and started writing—only for this to fall haphazardly into my lap. It was too perfect to pass up. The opportunity to let a composer show me exactly how to read the art that most influenced their practice: what could be more preposterous than that?

—

In the years I’ve known Tim McCormack, I’ve only ever heard him speak about two artists with true unmitigated reverence. The choreographer William Forsythe, whose tenure with the Frankfurt Ballet between 1984 and 2004 gave dance one of its most original revolutions and laid the groundwork for thinking abstraction in movement, is one. Tim learned to dance Forsythe in college, and it left an indelible impact on his body. He still moves with a vivid lightness, always on his toes, intentional, graceful, muscular, quick.

The other is the German painter Gerhard Richter, who, as it happens, just opened a 100-work retrospective in Berlin, where Tim and I have spent a week preparing his new open-form project deep terrane. When I tell Tim about the exhibit, he is aghast. He throws his arms up in shock. He looks giddy. All other plans, he says, can wait: we go tomorrow.

On the train to the Neue Nationalgalerie, Tim asks if we can hop off early for breakfast at Refinery High End Coffee, a sleek roastery not far from the Reichstag. They make his favorite cup of filter brew in Berlin, and though the bees have made a meal of the croissants in the glass case, he gets one of those as well. As we settle in on a bench outside the shop, still bleary-eyed from the night before, I see the opportunity and take it.

—

“Tell me about the first time you interacted with Richter.”

Tim lights up immediately. Even in the fog of sleep, he is an interviewer’s dream, animated and alert and capable of spinning his own threads far beyond the limits of the question. All I have to do is twist the wind-up a little bit and let it run; Tim does the rest himself. I’ve found that asking him for stories is usually a good place to start because Tim is always ready with a story. And usually three or four before that because he likes you to know the context for the first. Ultimately there are detours, shortcuts, side paths, tangents, secret doors, byways. He talks like his music, always in discovery. Also like his music, it takes patience: you have to get there.

“I actually do have a very hazy but distinct memory,” he jumps right in. “I don’t know how old I was but I want to say I was in the young teens. My oldest brother, Jeff, used to take me on outings: to art museums, my first Cleveland orchestra concert, that kind of thing. We were thirteen years apart, so it was sort of like…”

He pauses, searching through childhood for how best to describe his sibling.

“Big brother time?” I offer.

“Yeah, exactly. So I have a distinct memory of seeing what I now know as a post-1988 Richter Abstract Painting, which are the dragged paintings”—Tim is using Richter’s title here; the artist gave all the works made with this particular technique the obscure title of Abstraktes Bild, literally Abstract Painting—“And I just remember that it was clearly painted—though I didn’t think of this as a kid—that it was clearly touched, that a person made it. It didn’t operate as a painting like I was used to, there weren’t brush strokes, but clearly a human did something.”

“And it had this interesting density and layering to it, it was just cool. But I was too young to think like ‘who was this artist?,’ you know? I mean, I had probably seen Richter peripherally, in books or something, but it didn’t really register until I moved to Chicago in 2007 and could go to the free days at the Art Institute. They had an entire Richter room that represented many different sides of Richter… he’s a total chameleon, but a virtuoso in all of those things which is one of the sickening things about him.”

—

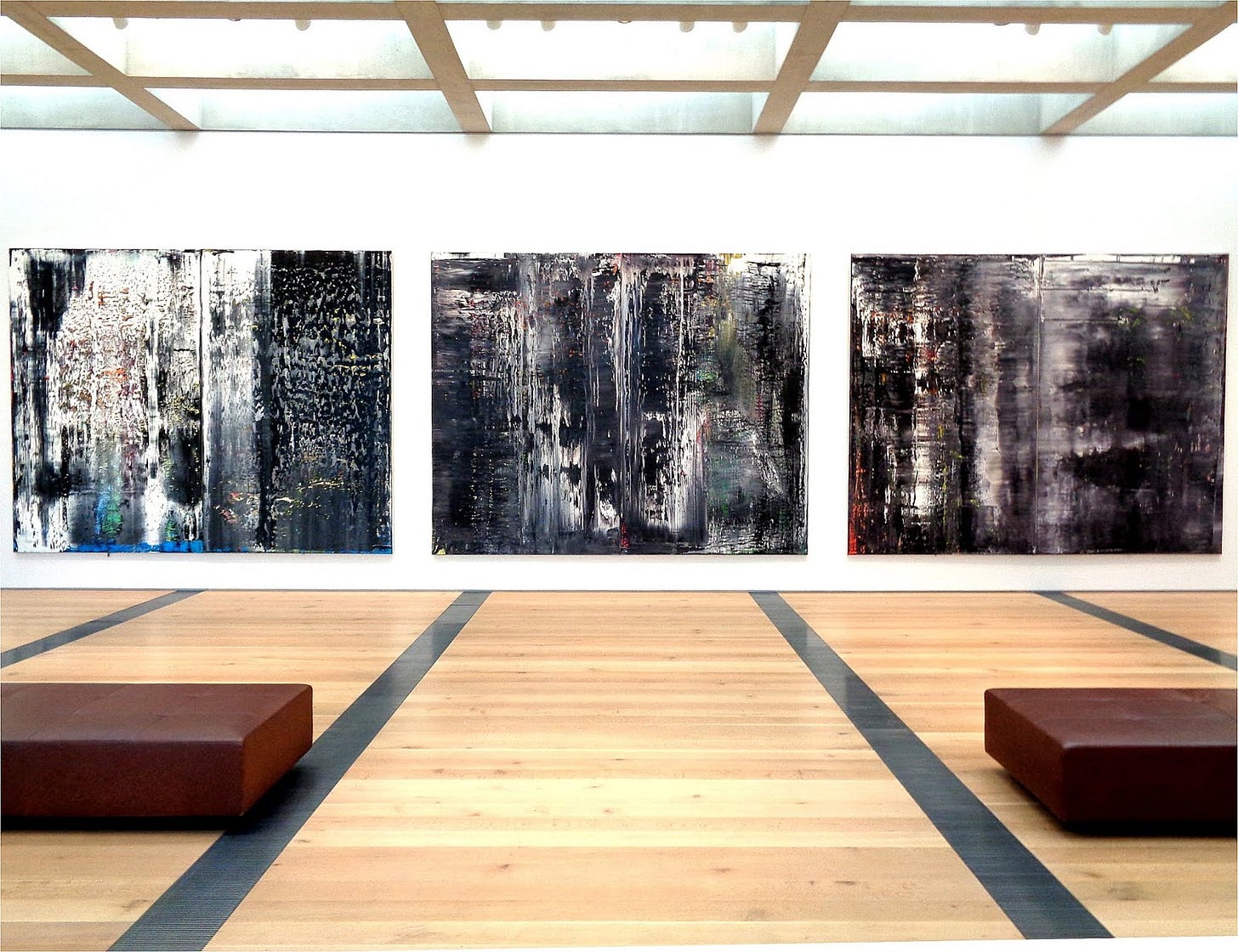

Richter, who turned 92 this year, is perhaps the most prolific and revered of living artists. Born in Dresden in 1932, he watched his father serve on the losing side of the Second World War and his family suffer harshly in the wake of defeat. As with so many children of the war, it’s a wound to which he’s often returned: the central painting in the Nationalgalerie exhibit is a triptych titled Birkenau, huge mottled canvases after photos taken from inside the camp. After defecting West from the Soviet-controlled GDR in 1961, Richter studied in Düsseldorf, where Josef Beuys oversaw a flourishing department. His early work, characterized by Fluxus tendencies, taught him a kind of master-of-all flexibility that has translated into maturity: his work spans representation, photography, abstraction, assemblage, watercolor, and print, all of which is among the most recognizable of our time.

—

Tim continues: “Anyway, Chicago has this… quad…? What’s a triptych but with four?”

He laughs, lingering to search for a word he can’t find. Coming up empty-handed, he improvises:

“Well, they have this four-painting-set,” he emphasizes his new hybrid, “called Eis (Ice). It’s an earlier post-1988 abstract—actually, I think it was 1988—and it’s just gorgeous. So complex and detailed and really vibrant. A lot of his Abstract Paintings have all this vibrant color work underneath, in the lower layers, and then, as he reaches what he intuits as ‘final stages’ he tends to really obscure that with grays and blacks and whites, so you just get these peeks, or, in more ecstatic moments, a corner will have ripped open into the inner body. The Eis paintings aren’t hyper-color like his earlier-80’s abstract dragged paintings, but they’re still vibrant in these really interesting ways. Each one of the four paintings are really distinct: each one has a different sense of form and movement and momentum within; each one—even though he’s making them with this really blunt instrument, a squeegee that’s the width of the painting—maintains a distinct identity that goes beyond color choice. But they also work together so well.“

“So whenever the Institute had a free day, I would go and spend hours in the Richter room, 20 minutes with the other paintings and the rest of the time parked for 20-30 minutes in front of each of the four Eis paintings and go one after the other, studying them. And studying them compositionally, really thinking about density as related to but distinct from texture. Of course, I didn’t have these words then, but the relationship between the local level—the moment, the place— and the global level—the total experience. And studying, attending to every detail, but sometimes letting the painting guide my eyes through it. So I was thinking about: ‘What is this density? What does it have to do with me and my aspirations? Why am I drawn to this? What can I learn from it? What does it mean for a musical or sonic texture that exists and changes over time?’”

“Of course painting in general, but especially these works, they’re temporal objects. Your experience with them develops, you are the one that changes. If you’re really with them, you can’t help but spend time with them. And I think something later on, that I then learned from Richter, was what I call proximity. As a composer, how close do I want my listener to feel to the source of the sound? And that can be a literal source or that could be a more orchestrational or sensual source, the thing in the music. So with Richter, and with these paintings, the local and medial are super important as well as the global level. The viewer is in control of their journey between them, it’s not just all the details on the page which you’re also moving through, but there’s an X-axis and a Y-axis that you the viewer are shifting through. And I, within one piece (especially recently, actually), I’m really thinking about that shifting degree of proximity. I want the listener to feel, in this passage, that the piece is distant but they’re yearning towards it, and I want in this moment to induce a sensation in the listener that they’re being drawn closer or they’re now suddenly enveloped.”

Tim has fully pivoted to music now: “The more I think about things, the more I think it goes back to the relationship and discourse between the local, medial, and global levels of a piece. It’s material, it’s decisions, decision-making, it’s form, it’s experiential: it ties the experience to the actual material and it’s the discourse between all of that, both between and amongst layers. That’s everything, that really is everything.”

“That’s form?,” I ask, hoping to clarify a term I’ve often heard him use but never forced him to define.

“Yes,” he says, “but form is not distinct from material, it’s not a container that material is put in. That’s sections, structure. Form is the tender contingency between those things.”

We look at each other and smile, soaking in the weight of those words. Tim giggles a bit, surprised at himself. Tender contingency has immediate traction for thinking through structures of experience. Conversations with him abound in phrases like this. In his private life, Tim tends towards intense introspection and hyper-scrutiny, and when he speaks he likes to mean exactly what he says. In search of specificity, he’s spent many years whittling a nuanced vocabulary of highly idiosyncratic terms that get at the heart of how he thinks about art. For this reason (and I tell him this often), I tend to think of him closer to an Éliane Radigue or a Robert Ashley than a notes-and-rhythms composer. For all the meticulous detail and inscrutable decision-making that informs his scores, it is only really by sharing space, meals, conversation with him that one can get inside his sensibilities. His language for articulating precisely how sound functions in his world is so fine-tuned and clear that you need his body in the room to fully know how a piece is supposed to go. Orality and trust is crucial to his process.

Returning us to Richter, I ask about this year he keeps referencing:

“You talk a lot about 1988 as a significant year in Richter’s paintings. What’s that change? What’s the shift?”

He smiles, and rebounds almost immediately. “The shift is like geologic, tectonic, it’s a huge shift. In the earlier ’80’s—he was dragging before 1988—it’s very vivid, vibrant colors and they’re just bluntly on display, so there’s no mystery to their relationship. Whereas in the post-1988 works, they’re much more concealed, but it heightens their vibrancy, it heightens their function and impact upon the total image and the experience. Also, pre-1988 abstract dragged paintings are, I think, weirdly more about process than post-. I say weirdly because the process for his post-1988 works is famous, the process itself. There’s an entire documentary about this. So yes, the process for the post-1988 works is important and celebrated, but the pre-1988 works lay the process really bluntly, bare. It’s about the gesture, there’s no mystery in it. You literally see what movements he used to make this thing. He stopped so short: he didn’t build up layers, he didn’t push through the thing to find something beyond. And around 1988, he painted — well, there’s two works in particular — Decke, which I selfishly titled a string quartet after but it’s not a bad piece so I don’t feel that bad.”

—

He’s right. Premiered at Harvard in 2013, the third mature string quartet is an astonishing piece. Somewhat uncharacteristically, it’s a short piece for Tim, only fifteen minutes long. (His recent music leans heavily on duration — your body is a volume, the string quartet that followed [also written for the JACKs, who have an album version of it coming out soon] clocks in at just under an hour.) But the score is quintessential McCormack. Meter and tempo are totally absent in favor of his carefully sculpted time-space notation, within which a complex web of red arrows guides each of the four performers to their auditory (and, because the detailed shading of the music is so quiet, often purely visual) cues. The music requires each of them to participate in an intense exchange of listening and trust by which they relate their own material to the mass form taking shape.

Tim took Richter’s technique very literally, deploying the four bows of the performers as a kind of Rakel, the squeegee-tool Richter uses in his paintings, dragging away at sounds to displace or smear their source of origin. The effect is of this intensely chiseled and rough-hewn cavern, soaked in darkness and dripping in salt-water. But it does not stay there. It pursues something deeper, something under and beneath the walls around it. Elsewhere, Tim describes Decke as “a weathered monolith, its surface and form eroded such that subsumed sedimentary strata periodically reveal themselves, to the point that the aural surface only suggests its corporeal form.”

—

“Is Decke the first Richter-inspired piece?”

“That’s a good question. I think it is. Right after I wrote Decke I wrote DRIFT MATTER, my cello solo, which is not a Richter painting—drift is a geologic term—but it was where I connected my interest in Richter, my touchpoints with Richter, and geology, geologic movement. Richter’s-squeegee-as-glacier carving the landscape, unearthing things, revealing things. Slow pushing though a thing, but then utterly changing as it progresses, slowly moving. I say slowly because—to get back to the question!—the pre-1988 paintings have a sense of speed to the gesture, or at least that’s how it’s experienced. Whereas in the post-1988 works, because the squeegee that he’s using is oftentimes the width of the canvas… bitch, all that paint?”

“All that paint,” I echo, grinning. I’m endlessly astounded by how quickly his erudition pivots into a distinctly queer humor without losing any of its gravitas. Referential humor—he can quote drag queens as fluently as Deleuze—is how he grounds his conceptual world in reality. We’ve lost hours of our lives to nightly viewings of Johnathan Lynn’s 1985 Clue, each time racing the other to a more nuanced exegesis of the film’s intricate inscrutability. Tim can rattle off every line of Madeline Kahn’s Mrs. White without missing a beat.

“All that paint!” He continues: “It’s creating, not suction, but a ton of resistance, and in the documentary you see him — I mean, these canvases are sometimes huge—you see Richter really using all of his strength to just move this thing, and it’s really a work-out. I’m not glorifying the effort, but what I mean is that it’s slow but effortful, slow with resistance, movement.”

“So yeah, Decke is a really interesting painting—I don’t think he has another one like it—in that the entire painting has no subcutaneous layers of vibrant colors: the entire painting is black white and grey. It’s just amazing. I didn’t know of Decke until after I’d really established my relationship with Eis. One of the things that really drew me to those was the interaction of color and layer, but with Decke there is no color, it’s just layer, it’s just elemental force, it’s just material and the traces of the making of it. It struck me as such a stark but poetic distillation of Richter’s activity — and this is one reason I’m attracted to noise. You could easily say most of his post-1988 abstract paintings are some visual representation of noise, but Decke specifically means blanket. You know I love my blankets, you know I love them, I love nests, I’m a nest-builder. And for me, noise is an amniotic interior, a safe, warm nest. So the title is really perfect.”

—

The two of us have been talking about nests a lot these days. Tim’s new voice solo, which comprised one-third of the program we did in Berlin and which I just reprised in Boston, is called nestbuilder, a hermetic web of softly spooling threads that ends in a haze of shimmering glass. When he’s in his own space—a spotless, modern apartment in Dorchester, all hard angles and skylights and muted gray-blacks—Tim is trailed from room to room by a mound of earthen blankets (his husband Tom, tells me they have a moratorium on new ones). When he settles on a spot, everything he needs is carefully arranged to be within arms-reach: books, iPad, snacks, a delicately-crafted cocktail from their curated wet bar. At all hours, the record player—a monumental slab of plexiglass carved down to a heavy disc and spun by a thin leather band—whispers an achingly slow soundtrack of shrouded, distant singing: Joanna Newsom, Perfume Genius, Fever Ray, Cocteau Twins, Grouper. These shadowed, sequestered ecologies that seep with a devastating sense of rest—this is where Tim’s music begins.

—

“And then after he did Decke (yes we’re still on the second question), he made this just stunning triptych called January, December, and November. The scale of these things are another level, but it’s stunning how once he painted Decke, how exponential and seismic his development of this technique was. Once he broke through, it was there.” Tim snaps for added emphasis. “Just like the Eis paintings, each one belongs to its own world, but the discourse they have amongst each other and the way they create a total experience, the form of the triptych, individually and together, is just stunning. The momentum of them…”

“The other thing is that these paintings are not only that particular sponged, porous layering, not just that particular look. There are moments when the painting really dissolves into itself, these patches of indistinct haze. I literally had a hallucinogenic experience when I saw January-December-November in St. Louis because of the complexity of depth and density. Earlier I was talking about depth and density in Richter as distinct from texture, but in these paintings he also finds a way to bring texture into that, heightening why they’re distinct. There are moments when you’re standing in front of this thing in a live space, and I felt like I could put my hand through it and there’s another dimension, but just in this zone, just in this one patch.”

“And that suggested, in my work, these places where something is established, something is being maintained, and then some thing within it shifts, or is recalibrated, or is very subtly added, or is removed. In these moments I want the barometric pressure in the room to change. I want one’s sense of time or space or proximity to shift, but in a way that feels like you’re part of the turbulence, gentle turbulence, just air moving. But it’s brought you somewhere: you’re moving forward but you’re also in this pocket.”

—

If you stay with Tim long enough, he’ll eventually use the words passage and clearing. They’re touchstones in his language and crucial to understanding how he thinks about form. As instincts, he can trace them back to his earliest pieces, back before he even had words to describe them. Now, however, he explains them like walking in a forest. Under cover of the canopy and surrounded by trees, your sense of movement is heightened by the rich proximity of detail. It is dark, but lush. Much is passing as you go. This is a passage, and it is only by pushing through them that you come across a clearing. In these spaces of barren vastness, the scale changes. You’re still moving at the same rate—the walking hasn’t changed—but it feels slower, endless beneath the wide and distant sky. The horizon is all you have to measure yourself against. Clearings, Tim says, are always discovered. They’re only accessible by transgressing a natural limit, a space beyond the space. They’re the place the sound takes you, the place that can’t be known before it’s found: once you’re in one, though, a clearing is only inevitable.

—

“So all of this I’m extrapolating from Richter in the first two years of him doing this technique. There’s so much in here. Even today I still love Richter’s painting, but I don’t have Richter on the mind in the same way. But I think part of that is because Richter, as well as Forsythe, as well as the Earth, these are.. uh.. people?.. that I, upon first confronting them or thinking about them in a certain way, I had an intuitive sense that I had a lot to learn from them, that a lot was relevant to me. So studying their work, and in the Forsythe case learning how to dance and learning Forsythe’s movement vocabulary and sensibility and actual putting that in my body—I never painted off of Richter but off of Forsythe I became a dancer—anyway, after spending years with these individuals and thinking about them and reading about them and embodying them, I learned a lot and they really helped me get to a point where they’re still relevant to my project but I don’t feel as though I need to think through them as a frame through which to understand my project. And more importantly, at least with the human artists, I don’t need to import them into my titles or —”

At this point in the recording, everything goes still. There is a short gasp from Tim, and then silence again, several long minutes of it, punctuated only sparely by sharp breaths of wonder and fear. A large black fly, beetle-sized and shiny, has tumbled out of the sky and landed with a clunk on the table beside us. Its tiny frame shudders uncontrollably as it rocks back and forth on its wings, caught in the throes of death and unable to flip itself upright. The spindle-thin legs seize in bursts and tortuous spasms that jolt the body in upsetting and grotesque contortions.

For the next three minutes, the two of us sit in near total silence watching the insect twitch itself to death. It is both terrible and intensely vulnerable, being with the insect in the violence of this moment. The ferocity of the moment is so heavy and labored that neither of us dares to move or look away: time stretches out, sinks into eternity. The last leg—the left prothoracic—takes an interminable amount of time to quit, as if the whole of that little insectoid life-force were still desperately concentrated in the lingering limb. At last the body freezes. Static sets in. On the recording there is an unsettled, breathless silence. And then, without warning, twin shouts of terror and the scraping of benches thrown backwards as the fly rights itself in a monstrous reversal of nature and soars off with a whine between our petrified faces. Gone as suddenly as it appeared. Tim curses audibly, visibly shaken. We stare at one another. We leave in a hurry. The recording ends here.

—

The train ride to the museum is unusually quiet, both of us preoccupied by the unsettling ominousness of the bug. By the time we’re walking up the steps to the Nationalgalerie, however, Tim is back to his bouncing excitement. He strides through the glass doors, making a beeline for the white-washed basement where the exhibit is taking temporary shelter (Richter’s ex-wife, the sculptor Isa Genzken, has an exhibit in the adjoining gallery), and the moment the paintings come into view he grabs at my arm and punctuates it with a characteristic “bitch!” As he had with the Eis paintings in Chicago all those years ago, he parks himself in front of each of a string of six Abstraktbilder, where I join him, sometimes for a half-hour at a time. These are more recent than the 1988 works—they date between 2017 and 2018—but there is still so much to grapple with. We take turns drawing one another’s attention to details. Tim, I notice, is immediately perceptive of changes in texture. He notes the places where the paint raises from the canvas, the edges where colors mire, and how small, peripheral occurrences ripple with global impact. I’m reminded of tender contingencies. And he is tender: Tim speaks to each painting with the gentleness of a living being, credits it with logic and behaviors and tendencies to be learned, loved, attended to. He emphasizes the time this process takes, shows me how to surrender to it, be guided by it.

By the last room we are exhausted and delirious, but calm also, and different for it. Two and a half hours have passed, though we hardly noticed: Tim and his music are like Richter that way too. You lose yourself in submission, overwhelmed by the duration of its hushed vulnerability. Time slips into abeyance under their watchful eye, and you cannot see another way except further, on, in.

I keep telling Tim I want to write a book with him, and though he’s agreed, we haven’t done anything about it yet. So I’ll let him have the last word. These are excerpts from a text he sent me some months ago about yours in the process of being absorbed, the piece he wrote for our Klangspuren collaboration with Schallfeld. They capture, I think, what it was like to stand before those mammoth canvases, covered in all that paint, and burrow headfirst into their folds with Tim at my side:

Slowly, softly, noisily,

seeking within itself.

Sinking into itself,

search of deeper hollows,

voids, clearings, openings.

Always pushing for a space beyond a space.

Always sinking inwards, underneath, within.

Subterranean spaces.

Sub-spaces.

The labor of surrender.

Obliteration, sublimation, absorption.

From one to the other.

To live through the experience is to live beyond it.

Search for a place from which you cannot go back,

because:

how could you?

—

Thanks for indulging a break in the schedule, and thank you to Tim, my stowaway, for letting me under your skin. I hope I’ve offered even a sliver of the endless joy that comes with calling you a friend.

Saunders/Atkins to follow shortly: expect something very different, probably more manic, definitely more conjunctions. Lots more. As in: too many more. In the meantime, keep an eye on tomorrow’s VAN Magazine for my review from Bucharest of the Enescu Festival’s Saint François d’Assise: my thanks always to Jeff Brown, who is the dreamiest editor you can imagine. And so much to come. Dorothy Molloy, Marcel Beyer, and Can Xue were all waiting impatiently on my doorstep after tour ended, each of which I had ordered (second-hand, of course) for some preposterous reason or another. I cracked open the Molloy last night, and can already see why Clara is so attached to it. Look out for more on that sometime in November.

To those of you who have donated or signed up for paid subscriptions in the last month, I can’t say thank you enough. This space is a joy to maintain and I’d do it for free, but your generosity makes being preposterous even more of a privilege. It means the world.

And as always, thanks for taking the time to read. Your time, attention, and commitment is so precious, and I’m lucky to be trusted with even a few minutes of it. If you’d like to offer thoughts, comments, opinions, or questions, know that you always can: this series is as much for you as it is for me.

you know this I love you

tb