How I Love You (i)

writing towards Enno Poppe and Marcel Beyer

I.

There is no writing on Enno Poppe. No writing, neither the doing nor the done of it. It has taken me six long months to reconcile that fact, but with every passing failure I am forced to confront the reality that his very good music that I like a lot is just not productively recuperable in language. It, in the very phenomena that are most pleasurable about it, prohibits a writing that would seek to think alongside it. I have never before known a music to do this. And so my gradual frustration at this crisis of language has morphed into a twisted fascination with the breach: Have I met the sheer limit of my meager abilities? Or is something else at play, an constructed irreparability barring his music from the question of being that every time falls short or grazes by it in the dark? Could a music be accused of intentionally evading inquiry? And, if so, what, then, becomes of the nature of my very real enjoyment of Poppe if the means I have to cast myself towards him prove again and again inoperable and precluded?

In the interest of locating the source of that conflict, I was forced to seriously rezone—or at least, more definitively articulate—the grounds on which I think I stake my work. I’ve decided I still subscribe to a loose chiral distinction separating “music criticism” (“critical theory as it pertains to music”) from “music theory,” one stemming from small differences in the orientation of their governing disciplinary question and its necessary arraignment in language. Music theory (put no doubt too simply) would ask how music thinks about itself. Sensual perception and receptive cognition being entwined with an endogenous musical logic, theory’s work has long been to untangle that logic in hopes of better understanding how it arises from—while in the same motion giving rise to—phenomena of human perception. Written language is a pure utility here: the somewhat inconvenient but necessary medium for public attestation whose rigorous and methodological facticity leaves little room for play and excess. (This might elsewhere be called jurisprudence.)

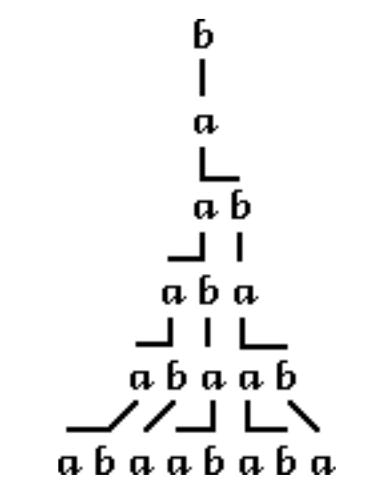

As perhaps the most idiosyncratic and recognizable voice in process-based composition to date, Poppe’s music plays overly nice with music theory. Since the early nineties, he has primarily modeled his organizational logic using a 1968 developmental algorithm written by Aristid Lindenmayer called L-Systems, designed for simulating the fractal and symmetrical growth of plants. In its most base form, the theory involves a simple formula of simultaneous replacement: given the terms a and b, and the rules a → ab and b → a, the following derivation is yielded through the first six strings (this example from Prusinkiewicz and Lindenmayer’s The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants):

Poppe can run varying strains of similar systems concurrently, often applied to different parameters, resulting in mass quantities of divagating material all generated from a single source. This is how the twin micro-elements of Trauben—piano chord and string glissando—can so quickly divaricate into enormous thickets without losing even a trace of their perceptional clarity; their botanical symmetry preserves always a reverse-engineer-able, cellular clarity. {Given chord and given gliss, etc. etc.}

—

That paragraph was very easy to make; its language is utilitarian, serving to explain, verify and formalize an absolute specificity of phenomena. But this is not yet writing.

—

Criticism, meanwhile—and, for lack of a better term, I tend to think of this as my arena—would concern itself with how music thinks about us. Operating within the providence of a metaphysics as opposed to a mechanics, writing becomes inseparable from the wager. As the sole available means for brokering the thought thinking thought of musical ontology, language is necessarily implicated as the active, speculative grounds on which an interaction between being and articulation is negotiated in accordance with the terms set out by the work itself. That last bit is vital: full of uneasy knowledge that its medium is not shared with its object, the heavy labor of criticism is to seek the impossible malleability of language that could enfold the music as other inside it without stooping to reduction or approximation. Put another way: I write in search of the national tongue we two alone speak, formed as it passes between us in our constitutive cohabitation; the music must always feel it maintains its fullest freedom on that terrain.

The undertones of love here are hard to overlook. The humility of a malleable language that would welcome an unknown, exterior sensibility to occupy its marrow is a submission only elsewhere found in sex and in love. Cixous knows this: “When I write I ask for your hand; with your hand I’ll go too far and I won’t be afraid anymore of not coming back. Without my knowing it, it is already love. Love is giving one’s hand”—and writing is the asking. Criticism in its ideal form would be a writing of/as love. Under the legislature of such a project, Enno Poppe is a delinquent and irrecuperable object. The question remains as to why.

To date, writers have litigated two solutions to approaching him, neither one satisfactory nor markedly generative. The first is ekphrastic: writing that suffers Barthes’s condemnation to the adjective and relegates language to sensual or onomatopoeic descriptors. These accounts typically rely on Poppe’s generous plasticity of gesture and abundance of instrumental color to supply mimetic vocabulary. From a Gramophone review of Fleisch: “In the opening movement, Donatoni-esque unisons and wonky homophonic passages give the impression of staircases leading nowhere. Tenor saxophone honks, electric guitar riffs, bongos pitter-patter—and it sounds like it’s just waiting for someone to start reciting beat poetry. The middle movement is a deep post-jazz blues, featuring umbral sax and shimmering hi‑hat.”

Often, these constellations of adjectives are extrapolated from the (seemingly) significant images provided in Poppe’s enigmatic titles. Even I’ve been guilty of this. While thinking about titles in the previous edition of this newsletter, I wrote that “the blunt atomic materiality of Enno Poppe is, before the music, in his titles: Öl/Speicher/Salz/Arbeit/Schrank. His predilection for these single, elemental words is their potential to generate endless chains of possible interpretations from a single semantic unit; his music does the same.” At the time, I believed that to be true—it may turn out to be, in the end—but I assumed, wrongly, that a taxonomical reading of his catalogue could ever generate productive exegesis. Imagine my surprise when Schott’s new book of Poppe interviews opened on an outright disavowal of that productivity. Asked to explain his early naming tendencies, the composer flatly dismisses titles as “overrated” and asks, as a dialogic principle, that they be avoided for the remainder of the book. His interlocutor, Michael Zwenzner, presses a bit, and Poppe gives not an inch: “For me, an important point is that titles like Holz [Wood] or Knochen [Bones] are decidedly anti-metaphysical, as I see music as something living and formative and find the material aspect of sounds to be what’s interesting. So the point is not at all that the sounds mean something, but rather that these sounds are interesting as such and have material value.” [What a quote; we’ll come back to it.] Zwenzner will try again later, at which point Poppe gets curt: Über Titel muss man, glaube ich, nicht reden, he says pointedly—I don’t think there’s any need to talk about titles.

Jettisoned of the safety of titular metaphor, the alternative solution has been to recourse onto higher theoretical ground and provide something like an antiseptic IKEA Assembly Manual: strip the whole to parts, offer a summation of its mechanistic construction in place of its lived experience, and pray that readers can put the thing together on their own. These accounts rely on the aural transparency of Poppe’s L-Systems as keys which, if you know them, unlock a satisfactory experience of the whole. Take the Festival d’Automne’s 2018 copywrite for Rundfunk: “Poppe’s music is built on cells, starting with simple unicellular units developing, for example, up/down/up, varied, extended, reversed, and set to different tempi.” This tells me exactly what takes place—leaving me where?

In short, we are torn unhappily between describing how it sounds and explaining how it works, neither one of which amounts to a loving writing towards that would ask for the music’s hand in return. When Barthes wrote the lover, he admitted description and anatomy were impossible: “So I accede, fitfully, to a language without adjectives. I love the other, not according to his (accountable) qualities, but according to his existence; by a movement one might well call mystical, I love, not what he is, but that he is.” We have not yet sufficiently solved for Poppe’s that-he-is. Even the ever-eloquent Simon Cummings of 5:4, having proffered a brief account that splits the difference, concludes that “to talk about [Poppe’s] Prozession in much more depth than this would probably be futile, and in any case do the work a disservice.” Poppe is fugitive, unwritable and unbreachable except by zones of language already willfully vacated of their own autonomous integrity.

Which is how he prefers it. Across the Schott interviews, Poppe goes great lengths to evacuate any potential assumptions of metaphysical productivity still lingering about his music. His claim—“I am an absolute representative of the autonomous concept of art”—is meant to deflect words: my sounds, he hinted earlier, mean nothing except themselves. In a glittering essay on Eric Wubbles (whose music is not dissimilar in its meticulous particularity), Seth Brodsky postulates that “there may be something useful in savoring the way [Wubbel’s music] deflects words, and in following their ricochets. Not least into larger theaters.” Poppe would appear to be advocating for a similar relish of refusal. “Explanations,” he says, “especially clearly formulated explanations of art, may provide some kind of understanding, but they are always just reductions.” To which he adds: “Words have something coarsening about them.” He’s doing it intentionally; language is set up here to fail.

This is because the foundational tenet of Poppe’s music is an extreme investment in sonic truth and verification that he terms “comprehensibility.” His organizational processes are not private generative tools to greater ends (see Evan Johnson): they are, themselves, the end. His systems are fully transparent, immediately trackable, and indicative of nothing except that process itself is underway. “My music,” he says, “is about observing processes and noting how perception works. If I initiate a process and let it run for a certain amount of time, my perception will tell me at some point that I have understood it.” Understanding is essential. Even at its highest density, it remains decipherable chaos which is, of course, not chaos at all, having not relinquished its reigns even an inch. No, there is never a moment when one loses oneself to Poppe’s music: there is no place to be lost.

By design, then, there are no metaphors or multiplicities, no aporias or mysteries, no open ends, no secrets, absolutely nothing in the music of Enno Poppe that could ever remain unknown. It will never cast signification back into a speculative realm of being where language would need to intervene. The music’s truth is itself, absolutely, and it would take a Borges-worthy book capable of replicating on paper each and every utterance of his music exactly as heard to achieve even an adequate proximity of that truth—which would, of course, be only the score. There is no introspective deduction available in the experience of his music. Clinical facticity and mutual corroboration is the entire game; it means only that it means:

Something doesn't gain meaning because I make any claims about it in program booklets, but rather because there is something to be perceived. Only through the fact that something is intentionally posited by me as a perceptual phenomenon does something arise that I believe to be intersubjective. That's the moment when I begin to enter into communication, first with my interpreter and, through the interpreter, with the audience. Even though there may be different levels of prior training, I believe in this communicative strategy. My interest is in communication—that is the most important thing for me.

(—although that last claim isn’t entirely true. Communication is one of three different attributes he designates “most important” at varying points across the book, the others being process—“The most important and crucial thing is processes”—and clarity—“Above all, it is about clarity.” Taken together, though, the triptych neatly underpins the compositional philosophy at play: a communicative clarity derived of process, expressive but without meaning.)

So if we take Poppe at his word that this is an “anti-metaphysical” music preeminently concerned with comprehensibility, understanding, communication, clarity, transparency, immediacy, and perceptibility (I might even say legibility if writing itself weren’t the thing at stake), we are also accepting the risk that it hides nothing. That everything is on the table. That it can and must always be known. And in doing so, we willingly surrender difference. For if I am to always know this music totally, there can be no being-Other with it. That smallest increment of difference would amount to a separation in which what I can never know enters irreparably into experience, and without this increment of difference, the love on which a writing can be founded becomes unsalvageable. Cixous’s own definition of love (of which she emphasizes “the work of art is the same”) is predicated on an unknown the very existence of which permits her to say “I love you”:

My heart beats from not recognizing you, from recognizing: I don’t recognize you, I sense that I don’t recognize you. (To sense that I don’t recognize makes my heart beat); what makes my heart beat is that something remains non-recognized, that I sense the unknown, that I keep it unknown. This is love. I will never know how I love you. I love you I don’t even know it. You will never know how I love you.

Enno Poppe’s devout denial of metaphysics in favor of processual transparency is a problem of precisely that unknown on which the Other of love is founded. Like Lanthimos’s The Lobster, I can name and ratify exactly what it is I love about you; contra Cixous, you will always know how I love you;—and is that still love?

There is no writing on Enno Poppe because the writing-towards of a criticism that would meet any music on its terms necessitates an opposite love that reaches out in return (“Love is giving one’s hand”), and this love, accordingly, requires something permanently non-recognizable to set the reach in motion. (Barthes: “estoy a oscuras: I am here, sitting simply and calmly in the dark interior of night.”) But there is no unknown in Enno Poppe. Poppe’s music, in its radical insistence on experiential verity, exposes itself always too much, becomes unsightly and frightful and too honest in its leering, gigantic proximity. And it is at that very moment that it forecloses on the offer of alterity and, by so doing, rejects, willingly and knowingly, even the possibility of the amative as a productive route of access.

In short: I do not love you. To write “I love the music of Enno Poppe” would be the unthinkable limit of music criticism because his music lacks the conditions necessary for the word “love” to be spoken at all. It does not make of me an other; it keeps me beholden to its authentication without permitting even an ounce of difference in which I might find myself lost in its dark interior. It is light, nothing but light, fluorescent, excruciating, clarifying light. I cannot fail to recognize it, and so I cannot love it, and so I cannot write it.

There is no writing Enno Poppe.

From whence, then, if not love, comes this strange pleasure?

II.

With only a single work’s exception, every word Enno Poppe set between 2002 and 2015—three operas, a chorus-orchestra behemoth, two chamber excursions, and a song’s worth—came from Marcel Beyer. The former music contributor for the punk-rock review Spex (a job that left him, Poppe says, with both an excellent ear for sung text and an enviable vinyl collection), Beyer is best known today as one of the great literary excavators of the trauma of post-war German memory. Born in Dresden and raised among the vestiges of East Germany’s architectural and linguistic ruin, Beyer’s writing unfolds in similarly non-duplicitous spaces where onomasiological peculiarity—jargon, regional dialect, archaism, uncanny translation—meets and troubles history; or, as he puts it, “that dizzy whirl of time and place overlapping across language.” His novels fixate on characters prepackaged with their own unassimilable vocabulary: an ornithologist in post-war Dresden; a sound technician documenting voices in Hitler’s bunker; opera singers and Luftwaffe pilots flying through the Spanish Civil War; an apiarist with a passion for calendars. It is the specialist’s terminology that attracts him; the proper identification of discrete phenomena reveal hidden intellectual tunnels between otherwise disparate histories, recasting the present through new and unstable lenses (Hitler’s death observed as a study in laryngeal fatigue, for instance). “The poetic is the precise,” Beyer’s self-projected narrator writes in Putin’s Postbox; “And precision of observation yields mysterious words.” Competing etymologies; the alienation provoked by extreme specificity; the tendency of words to unconceal cultural orientation: these are his perennial fascination.“Words,” he says, “isolated from their language environment, snapped up, not understood—can be fiery nuclei.”

From a technical standpoint, this morphemic fetish lends itself extraordinarily well to Poppe’s cellular L-systems. While working on “Wespe,” for instance, Poppe requested a poem of predominantly one- and two-syllable words that could retain auditory clarity when funneled through endless small glissandi. Beyer responded by thematically equated the wasp with language itself, allowing him to juxtapose anatomical lingo (palate, pharynx, tongue) with insectoid descriptors, stitched through by idioms specific to decade and nation (eighties, nineties, year, German, but also Nesquik and The Edge). These local contiguities allow for the highest possible valence of significance not by acoustic distinction—the musical material is almost all derived from the same piquant cell—but by the invisible, subtly shifting polysemic baggage underneath it. Every word bears different weight, and one feels, rather than knows, the rhythm of the changing angles and etymologic depths with each new syllable. This magnified semantic minutiae is perhaps not so far from Poppe’s own articulated desire for a musical approximation of too-small-to-be-described and yet immediately-understood facial nuance, “the smallest changes in expressive qualities that cannot be verbalized.”

—but we are back again at explanation. Beyer and Poppe have amenable intellectual interests; hardly a surprise. This tells me nothing about being with their work.

No, I want to attend closer to how Beyer treats the question of the other. Specifically, I want to linger with the nauseating central passage of his second novel, The Karnau Tapes. It is, appropriately, a book about sound. Hermann Karnau is an acoustician working under the Nazi regime whose secret, talismanic dream is to map every corner of human utterance. Soft-mannered and secluded, familiar with children (the book entwines his work with the parallel and at times overlapping lives and deaths of the children of Joseph Goebbels), affectionate towards his dog, conscripted neither against his will nor by any especially strong doctrinal alignment, he tacitly pursues the all-too-familiar academic allure of resources and stability that even a vile government can offer. And so Karnau is offered to us as a morally ambiguous but largely trustworthy narrator whose scientific credentials and empathetic labor surrogate him with a presumptive humanism. His fidelity to and investment in his research—and in particular to such a deeply embodied and expressive labor as human sound—performs that famous kind of intellectual maneuver of supplementary ethics: because he studies human expressions of selfhood, we automatically assume he cares about people and their bodies.

Mid-way through the book, Karnau is invited to lecture on acoustics for a symposium at the Dresden Museum of Hygiene. In a fit of scholarly frustration with the meager work of his colleagues, he advances the extreme theory that voice—“the link between the inner man and the outside world”—marks the final and ultimate frontier for their beloved Germanization. As the source of the soul, Karnau argues, the vocal folds can retain marks of cultural differentiation and rebellion long after blonde hair and sturdy posture are ubiquitous. Conformity to the Aryan Race—Karnau never indicates allegiance to the idea, merely criticism of the theories animating its execution—is thus not complete without linguistic intervention, and in the heat of the moment he proposes going so far as to surgically intercede if necessary to achieve a sufficient German.

In the passage that immediately follows, Karnau will be given the institutional green light to test this thesis at the limits of perceptible expression. Under the Nazi flag (though it is still his map of utterance that privately motivates him), his research will shift from a peripheral obsession of stolen observation (secreted in his bedroom listening weepy to sound samples on shellac) to the controlled center of a dark wet basement laboratory. It is in this bleak dungeon, where subjectivity at the absolute margin of permissible truth poses an injunction to pleasure, that the specter of Poppe himself—the Poppe who says “For the composition process in my laboratory, I wear a white lab coat while working”—becomes uncannily familiar. I’ve reproduced a longer passage, the narrative tone of which marks a considerable departure from the equivocating meekness of Karnau’s earlier appearances. Watch how language both shields and undermines the violence taking place, what darkness the felicity of ecstatic description masks behind it:

No use swabbing away the blood, it tints the gums like rouge, laps around every tooth in fine skeins. A complete set? A full house, dentally speaking? The jaws are clamped apart in the usual way to avoid damaging the enamel. Slight prognathism. Several microphones are needed to investigate this remote and hitherto unexplored area. Four are focused on the test subject from different directions. A fifth, secreted in the immediate vicinity of the sound source, serves to pick up special frequencies. It is continually modulated while recording is in progress so that certain features of the voice can be brought out on tape with precision.

The larynx, subjected to a weak and far from dangerous electric shock, gives an involuntary jerk. Will the voice go racing up the scale, into the very highest register? No, it subsides before it can do so. Murmurs uttered in a normal voice and repeated clicking sounds produce some very nice shadows. Then, slowly, barely perceptible at first, comes a dark, reddish glimmer, then pale violet, then a bright, sky-blue vocal shade. Is the light, the sound, already fading? As the larynx subsides and relaxes, so the voice becomes deeper and hoarser and displays a growing tendency to vibrate. The subject is still inclined to breathe from the thorax. Jaw movements are observable, and instinctive lingual contractions scour the gums. The more violent these movements, the more copious the flow of saliva. The subject tries to expectorate, but the threads of spittle run down his chin, mingled—so far as one can tell in the gloom—with blood. Here and there the blood picks up a ray of light and carries it along. Thin, diffuse and flickering, it weaves a pattern in the darkness.

[…]

Expanses of shadow alternate with others bathed in the spotlights’ glare. The smooth, fine-pored area stands out against its rough, uneven setting, where the musculature of the neck can be discerned when the chin is raised. Is that gooseflesh? No, just stubble on the edge of the ill-shaven jaw. The pink skin looks like a wound in the midst of that expanse of curly black hair, that stubborn canine fur which the razor has failed to slice off flush with the pores. The bare throat is motionless, exposed to a beam of light so dazzlingly bright that the illuminated area looks almost white. Rubber gloves squeak as the surgeon pulls them on. A final inspection of the clamps to ensure that the chin cannot suddenly sag, then the first incision. The open epidermis, the muscle texture, the blood that trickles over chin and shoulders, matting the fur. “Are you through yet?” A clamp is inserted in the throat. “More light, I can’t see a thing.” Next, the windpipe—a faint, rhythmical breeze plays over the surgeon’s fingers. Now to insert the scalpel in the narrow aperture and tackle the larynx itself. (pp.126-128)

Until now, we have implicitly trusted Karnau’s rationalist and empathetic candor. Here, however, the irreparable mark of intentional, senseless violence arrives to cleave him of that trust—only it fails to do so adequately. The sharp rise in Karnau’s linguistic performance, the result of both clinical specificity and rapturous confidence, enters at exactly the moment when ethical alterity and empathic difference are at their most immediate and volatile. Another life is vulnerable and trembling in his hands, and yet he is safeguarded from being in any way affected by it. So much does the textual tenor raise that we do not (or barely) see the cruelty of nonconsensual vivisection—of torture—taking place under his watch, hidden as it is behind a virtuosic objectivity (note Karnau’s twin tendencies of ekphrasis and anatomy) that reveals itself, finally, as caring not a little about the Other. Karnau, in this moment, unconceals a complete voidance of ethics, and yet he miraculously does not earn our abjection. He remains, in his easy trespass of soft epidermal boundaries through the decisive need to leave no facet of being unknown, in frightening intimacy with us.

When everything is on the table, bathed in fluorescent light and bare against the cold planar metal, absolutely nothing of being remains unknown except darkness itself. The only violence here is the one being done to violence. This is not literature’s traditional devastation of disaster in the diminishing act of its written capture. Instead, cruelty itself is mercilessly modulated into the scientific-poetic, forced to disavow its inhumanity in favor of abstract figuration and objectivity under the sign of the human. Submitting expression to clinical transparency veils only an awareness to any cruelty as such that could reinstall morality in one or another direction. Karnau receives neither disgust nor pleasure from the operation, and it is because of that failure to orient pain that he is permitted an enjoyment of the details of being—light on blood, the hiss of breath over the fingers—otherwise prohibited by an ethical existence. The very refusal to accommodate empathy allows him access, in language, to an act everywhere else impermissible by writing. This poetry in thrall to expressive precision without an ethics of alterity is thus revealed as what it always was: a cruelty whose singular pleasure is the unholy beauty of a forbidden truth accessible only by the violent suppression of cruelty itself.

Which bring us back to the strange pleasure, the not-love of Enno Poppe. In its parallel desiccation of the other of being, Poppe’s music encourages an equivalent pleasure, one derived from no-longer-being-beholden to ethical separation. The thrill is precisely the music’s audacious destruction of its boundary with myself, its assertion of itself too close too comfortably within my Otherness. Here, the invasive brutality of ontological unity; I am left only to survey the masochistic beauty of the complete obliteration of any system that would separate me from it.

This is not Cixous’s hand of love that reaches to be grasped. It is another hand. This one, too, would reach out towards the other, but it overreaches, bent on confirming too much the “I am” of the one that stands before it. And yet the trespass is welcomed, assisted, tolerated, enjoyed even, lawlessly returning my alterity to me at the moment it most definitively ruins it. It is the dirty finger that dares fish for absolute truth in the open wound of the Other (warm flesh, soft fold, the squishy tissue, damp cavern, strange feeling, your too-much-other the same inside me). Or, as Mieke Bal puts it in a text that echoes eerily with Cixous, the same text that gave this newsletter its name: “inside the wound, a labyrinth that is only skin-deep yet creates an altogether different, inner world with its own time, its own heartbeat.”

These are endlessly generative problems. Enno Poppe’s music backs criticism into unsettled corners where the reach of love, removed of any promised object, must confront its own pure gestural form. We have only begun scratching the surface of what might be gleamed by installing a metaphysics where Poppe insists there is none. I admit to enjoying (but not loving) his music intensely; from where if not from an illicit thrill at the warm fleshy limits of the ethical, a pleasure derived from overstepping the violence of the separation of the Other, might this awful pleasure come?

Is an ethical critique of violence necessary?

—What a question.

—

This calls, I think, for a Part II. Next year, I’d like to return at length to these problematics, but there it will be in the context of a rare ménage à trois. Despite Beyer’s own proclamation that “central books: that is, those everyone can agree on, have never much interested me,” the duo’s second opera, 2004’s Arbeit Nahrung Wohnung, was an adaptation of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in structural reverse. With Derrida’s second Beast and the Sovereign lectures—all about Crusoe—as a fulcrum, I want to linger a bit between boredom, simulacra, and archaism on the one hand and between Poppe, Beyer, and Defoe on the other as a means for thinking about the problem of critical productivity in Poppe and his operas. All in good time.

Before then, however, I thought we’d take a departure from our usual bookish programming and look into a collaboration both non-literary and (at least by new music terms) historical (read: dead). Next edition I’ll be thinking about what Louis Andriessen and Peter Greenaway saw in one another, with three operas and a film to their shared name. (Mostly it’s an excuse to rewatch The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover while listening to De Materie; and who can blame me?) On Greenaway, I’ll be drawing supplementary material from these two texts. After that, books return, with Olga Neuwirth and Elfriede Jelinek on the desk. Lots to say about both pairs, I hope you’ll consider returning. For now, je t’embrasse and thanks always for getting this far—

you know this I love you

-tb

References:

The Marcel Beyer quotes are sourced from The Karnau Tapes, translated by John Brownjohn (New York: Harcourt and Brace, 1997); and from Putin’s Postbox, translated by Katy Derbyshire (Berlin: V&Q Books, 2022). All Enno Poppe quotes not otherwise attributed are from Zwenzner’s Klappentext: Gespräche mit Enno Poppe (Mainz: Schott Music GmbH & Co., 2023). Translations are my own. Hélène Cixous quotations come from “What is it o’clock?,” translated by Catherine A.F. MacGillivray and found in Stigmata: Escaping Texts (New York: Routledge, 1998), 57-83. The Barthes excerpts are from A Lover’s Discourse, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978). The Mieke Bal line is from Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). And the final italics belong to Eugenie Brinkema’s Life-Destroying Diagrams (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022).

Housekeeping:

Welcome back to Preposterous Reading. As I said at the beginning, this text was devilishly tricky to get right, and between prior writing commitments and too much time on and off planes, it’s been a long journey to completion; thanks for your patience in the interim. Just a few brief announcements on other upcoming activities:

▪ Quite a bit of new VAN material coming out in the following month or so, including an essay (out today!) on queer musicology at 30. Forthcoming pieces on epistolary possession, Hervé Guibert, and Michael Finnissy; and losing your head to the music of Kelley Sheehan. Sign up for VAN’s weekly emails (and subscribe if you have the means!) to get those pieces straight to your inbox (thanks, always, to Jeff Brown).

▪ For those of you with institutional access, several new TEMPO reviews forthcoming, one on native Detroiter and permanent weirdo Lucia Długoszewksi, and one later this year on this especially beautiful album for Partch fans (thanks, always, to Heather Roche).

▪ And for anyone in Boston environs, I’m giving the opening lecture for Divergent Studios. Titled Seated at the Throat: Attenuation, Silence, Body, I’ll be thinking about ethics, pain, and extremity in the solo voice, with interleaved performances of music by Chaya Czernowin, Evan Johnson, and Timothy McCormack. It’s free an open to the public, Tuesday June 25, 1:30 p.m. in Pickman Hall; I hope you’ll come.